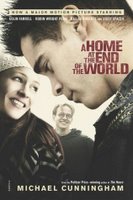

Cunningham, Michael. A Home at the End of the World. New York: Picador, 1999.

This novel was unusual in that it was only minimally invested in the gay experience, at least in comparison to the others I’ve read thus far. This is probably because Jonathan, its gay character, is only one of four first-person narrators—the others being his friend (and short-lived sexual partner) Bobby, his roommate Clare, and his mother Alice. Jonathan’s coming out isn’t ever dramatized or made a part of the plot. In his passages of narration, he describes his coming to the realization of being gay almost exclusively in terms of Bobby. He comes to realize that he loves Bobby, and only later, living apart from him in New York, does he identify as gay. At one point, Alice catches the two of them together, but this never leads to a discussion between them. Jonathan’s is a family not much able to communicate.

This novel was unusual in that it was only minimally invested in the gay experience, at least in comparison to the others I’ve read thus far. This is probably because Jonathan, its gay character, is only one of four first-person narrators—the others being his friend (and short-lived sexual partner) Bobby, his roommate Clare, and his mother Alice. Jonathan’s coming out isn’t ever dramatized or made a part of the plot. In his passages of narration, he describes his coming to the realization of being gay almost exclusively in terms of Bobby. He comes to realize that he loves Bobby, and only later, living apart from him in New York, does he identify as gay. At one point, Alice catches the two of them together, but this never leads to a discussion between them. Jonathan’s is a family not much able to communicate.So while it’s a coming-of-age story, it’s hard to read it as a coming-out story. Jonathan’s sexuality doesn’t lead him to who he is, it’s just a part of his identity. What the book is mostly concerned with is family and the kinds of families people form. Early in Bobby’s life, his brother dies accidentally and his mother commits suicide shortly thereafter. When his father dies after his graduation from high school, he moves in with Jonathan’s mom and dad, considering them as much his parents as any he’s ever had. Jonathan, meanwhile, has moved to New York City and begun living with Clare, a woman about ten years older than him. Their relationship is very often that of siblings, but the two of them make lazy, half-serious plans to have a kid together someday. To stay brief, Bobby eventually moves in with them, ends up sleeping with Clare, and they have a child together. Jonathan tries to leave but finds that he equally loves Clare and Bobby, and the three of them move just outside Woodstock to raise the child together.

I thought it was going to be a book about redefining and restructuring family, and it was, but I was surprised by the ending, in which Clare leaves with her baby and doesn’t come back. A baby should be with her mother, she believes, and has every right to take the child and raise her on her own. Much in the writing and structure of the book makes this seem inevitable and thematically sound. In that sense, it’s a pretty conservative book. The radical thing to do, it seems to me, is end the novel with Rebecca, the baby, having three parents living in harmony with one another. In the end, it seems Cunningham is trying to say that people often try to (re)create families of their own, but that these can’t succeed. Families, of any stripe, are doomed for destruction.