This book details a love triangle between an older bachelor, a younger married man, and a dog, Evie. The title, then, is pretty clever. Despite the older man's narrating the novel, i.e. using "I" throughout, the pronoun used in the title is "we". The plural signifies any two points of the triangle, for indeed, all persons think the world of all persons, and yet jealousy comes into it quite naturally, destroying whatever potential harmonies could come of all this.

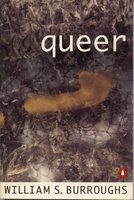

Also destroyed is Frank, the older man/narrator. He ends up with Evie in the end, the dog he spent time with only to get closer to the younger man he really loved. This is becoming a difficult thread to deal with in my reading of late. Time and again I've read books where an older, "gayer", upper-class man is in a consuming love with a younger, "straighter", lower-class man. Why is this such a staple in the 20th-century gay male canon? I imagine Forster, Isherwood, Burroughs, Ackerley, et al. were just living out their fantasies through fiction, a tradition spanning all genders and gender types, and without getting too much into it, it's clear that there's something very alluring about youth, about people who sit way out at the extreme ends of the traditional gendered-behavior continuum, and about people who are forced through lack of ability or interest to allow you to do all the thinking for them.

No book yet in the 1900s has ended with a central gay character overcoming this trap of fantasy.* Of course, I've only read up until the 1960s, after which gay subcultures come out fully into the public sphere and masculinity becomes expanded in scope to include more people than "men who prefer sex with women." Here's how

The Joy of Gay Sex, 3rd ed. puts it. Well, I was going to quote it for you, but while

TJOGS is pretty much a godsend for any closeted gay boy wanting to come out, full of plainstated truths and incredibly helpful advice (in between all the "hott" "pics" and how-to's along the lines of the original

JOS's kama-sutra-y stuff), the language of these passages tends to be a bit too...unbearable out of context, I'll say.

To love men is to love whatever it is that is "the masculine", and for most gay men—well, for all of us—what is attached to "the masculine" has for so long been one small set of objects and images that what else can you expect us to gravitate toward, obsess over, and write about?

---

*It's interesting that Forster's

Maurice, the first major gay novel written in the 20th century, resolves its plot with such a relationship, treating it as a kind of salvation whereas writers after him portray it as a trap.

This novel is greater than most others I've ever read. It deals with money, law, medicine, religion/the clergy, inheritance, property, farming, railroads, love, gypsies, and more and more and more. It is the exact wrong novel to read in a week's time.

This novel is greater than most others I've ever read. It deals with money, law, medicine, religion/the clergy, inheritance, property, farming, railroads, love, gypsies, and more and more and more. It is the exact wrong novel to read in a week's time.